X

Site

Searches content on sportslib.net based on your keyword.

Video

Searches for video content based on your keywords.

Board

Searches the Football Message Board for content matching your keywords.

Chapter 13. football (Soccer) tactics and skills > Kicking advanced (Volley, Bicycle kick, Spin kick, Rabona, Scorpion kick.)

Chapter 13. football (Soccer) tactics and skills > Kicking advanced (Volley, Bicycle kick, Spin kick, Rabona, Scorpion kick.)♣ Volley (association football)

A volley is an air-borne strike in association football, where a player's foot meets and directs the ball in an angled direction before it has time to reach the ground. A volley can be extremely hard to aim and requires good foot-eye coordination and timing. The half volley is a similar concept, but occurs when the ball has just bounced from the ground rather than is in the air.

Volley

In general, the volley requires that the player strike the ball with the front of his foot, with the toes pointing downward, ankle locked, and the knee lifted. It is important for most applications to keep the knee high over the ball when struck, and lean slightly forward to keep the shot downward. Doing so imparts a great deal of topspin and prevents the ball from flying wildly over the goal if done correctly. Because of the power and spin imparted on the ball, the shot can follow an unpredictable path to goal and prove difficult to defend against.

Used offensively, the volley can play a crucial role in scoring straight goals. Since a volley occurs when the ball is in the air, they often occur in front of goal as a result of a cross or a corner. In this instance, one attacking player passes the ball across the goal in the air, and the other player (either standing in place or in motion) strikes the ball with his foot before it hits the ground. This is advantageous over a normal strike in that the player does not need to trap the ball, taking an extra touch and allowing the goalkeeper a few extra seconds to react. Generally, the ball is struck on the laces with the toe pointing downward towards goal, though variations such as the bicycle kick or scissors kick in which the player's body moves in acrobatic fashion are occasionally employed, much to the delight of spectators.

Used defensively, the volley can quickly clear the ball from play and allow the defending team to recover their position. While less accurate and harder to execute than a normal long pass, the volley is useful for clearing balls that are bouncing towards or away from a defender because the defender does not need to trap the ball or change directions if they are running towards his own goal.

The volley is used less often for passes, as it is harder to control, though it can often be used to flick the ball on to another player. In this use, the strike is softer and more controlled than either the shot or the clearance. Also, the inside of the foot, outside, or even the heel may be used to flick the ball off of a volley. When the heel is used to volley the ball over the player's head (from back to front) it is often referred to as a "donkey kick".

Half volley

The term half volley is also commonly used, which is when the ball is kicked immediately after it hits the ground. A half volley may be better for situations when a volley can't be done because the ball is too high and the player wants to get a more accurate shot. An example of a half volley is Didier Drogba's goal with Chelsea against Liverpool in 2006. He controlled the ball with his chest from a long pass, then turned and took a shot with his left foot from the penalty arc that went to the bottom left corner.

♣ Bicycle kick (association football)

In association football, a bicycle kick, also known as an overhead kick or scissors kick, is an acrobatic strike where a player kicks an airborne ball rearward in midair. It is achieved by throwing the body backward up into the air and, before descending to the ground, making a shearing movement with the legs to get the ball-striking leg in front of the other. In most languages, the manoeuvre is named after either the cycling motion or the scissor motion that it resembles. Its complexity, and uncommon performance in competitive football matches, makes it one of association football's most celebrated skills.

Bicycle kicks can be used defensively to clear away the ball from the goalmouth or offensively to strike at the opponent's goal in an attempt to score. The bicycle kick is an advanced football skill that is dangerous for inexperienced players. Its successful performance has been limited largely to the most experienced and athletic players in football history.

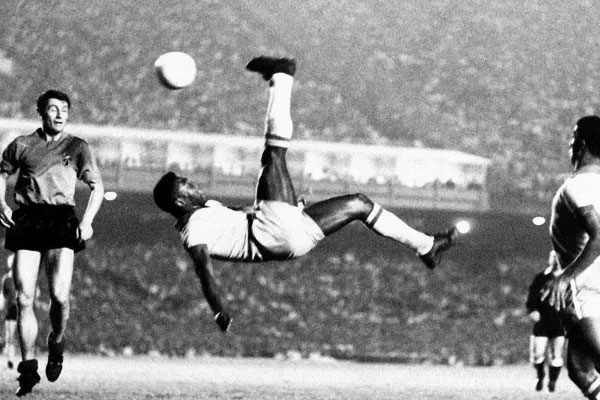

Labourers from the Pacific seaports of Chile and Peru likely performed the first bicycle kicks in football matches, possibly as early as the late 19th century. Advanced techniques like the bicycle kick developed from South American adaptations to the football style introduced by British immigrants. Brazilian footballers Leônidas and Pelé popularized the skill internationally during the 20th century. The bicycle kick has since attained such a wide allure that, in 2016, FIFA (association football's governing body) regarded the bicycle kick as "football’s most spectacular sight".

As an iconic skill, bicycle kicks are an important part of association football culture. Executing a bicycle kick in a competitive football match, particularly in scoring a goal, usually garners wide attention in the sports media. The bicycle kick has been featured in works of art, such as sculptures, films, advertisements, and literature. Controversies over the move's invention and naming have added to the kick's acclaim in popular culture. The manoeuvre is also admired in similar ball sports, particularly in the variants of association football like futsal and beach soccer.

Name

The bicycle kick is known in English by three names: bicycle kick, overhead kick, and scissors kick. The term "bicycle kick" describes the action of the legs while the body is in mid-air, resembling the pedalling of a bicycle. The manoeuvre is also called an "overhead kick", which refers to the ball being kicked above the head, or a "scissors kick", as the technique reflects the movement of two scissor blades coming together. Some authors differentiate the "scissors kick" as similar to a bicycle kick, but done sideways or at an angle; other authors consider them to be the same move.

In languages other than English, its name also reflects the action it resembles. Sports journalist Alejandro Cisternas, from Chilean newspaper El Mercurio, compiled a list of these names. In most cases, they either refer to the kick's scissor-like motion, such as the French ciseaux retourné (returned scissor) and the Greek psalidaki, or to its bicycle-like action, such as the Portuguese pontapé de bicicleta. In other languages, the nature of the action is described: German Fallrückzieher (falling backward kick), Polish przewrotka (overturn kick), Dutch omhaal (turnaround drag), and Italian rovesciata (reversed kick).

Exceptions to these naming patterns are found in languages that designate the move by making reference to a location, such as the Norwegian brassespark (Brazilian kick). This exception is most significant in Spanish, where a fierce controversy exists between Chile and Peru—as part of their historic sports rivalry—over the naming of the bicycle kick; Chileans know it as the chilena, while Peruvians call it the chalaca. Regardless, the move is also known in Spanish by the less tendentious names of tijera and tijereta—both a reference to the manoeuvre's scissor-like motion.

Execution

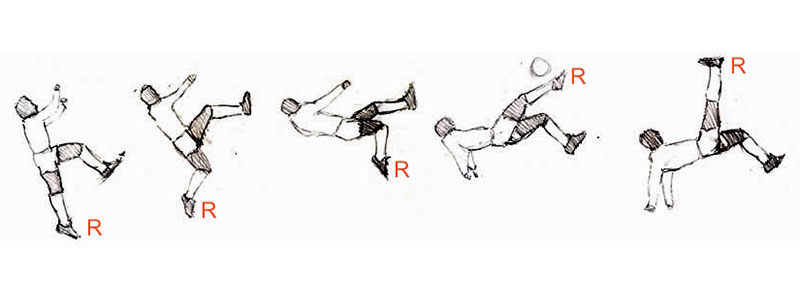

A bicycle kick's successful performance generally requires great skill and athleticism. To perform a bicycle kick, the ball must be airborne so that the player can hit it while doing a backflip; the ball can either come in the air towards the player, such as from a cross, or the player can flick the ball up into the air. The non-kicking leg should rise first to help propel the body up while the kicking leg makes the jump. While making the leap, the body's back should move rearwards until it is parallel to the ground. As the body reaches peak height, the kicking leg should snap toward the ball as the non-kicking leg is simultaneously brought down to increase the kick's power. Vision should stay focused on the ball until the foot strikes it. The arms should be used for balance and to diminish the impact from the fall.

Bicycle kicks are generally done in two situations, one defensive and the other offensive. A defensive bicycle kick is done when a player facing their side's goal uses the action to clear the ball in the direction opposite their side's goalmouth. Sports historian Richard Witzig considers defensive bicycle kicks a desperate move requiring less aim than its offensive variety. An offensive bicycle kick is used when a player has their back to the opposing goal and is near the goalmouth. According to Witzig, the offensive bicycle kick requires concentration and a good understanding of the ball's location. Bicycle kicks can also be done in the midfield, but this is not recommended because safer and more accurate passes can be done in this zone.

Crosses that precede an offensive bicycle kick are of dubious accuracy—German striker Klaus Fischer reportedly stated that most crosses prior to a bicycle kick are bad. Moreover, performing a bicycle kick is dangerous, even when done correctly, as it may harm a startled participant in the field. For this reason, Peruvian defender César González recommends that the player executing the bicycle kick have enough space to perform it. For the player using the manoeuvre, the greatest danger happens during the drop; a bad fall can injure the head, back, or wrist. Witzig recommends players attempting the move to land on their upper back, using their arms as support, and simultaneously rolling over to a side in order to diminish impact from the drop.

Witzig recommends that footballers attempt executing a bicycle kick with a focused and determined state of mind. The performer needs to maintain good form when executing the move, and must simultaneously exhibit exceptional accuracy and precision when striking the ball. Brazilian forward Pelé, one of the sport's renowned players, also considers the manoeuvre difficult and recalled having scored from it only a few times out of his 1,283 career goals. Due to the action's complexity, a successfully executed bicycle kick is notable and, according to sports journalist Elliott Turner, prone to awe audiences. An inadequately-executed bicycle kick can also expose a player to ridicule.

History

Football lore has numerous legends relating when and where the bicycle kick was first performed and who created it. According to Brazilian anthropologist Antonio Jorge Soares, the bicycle kick's origin is important only as an example of how folklore is created. Popular opinion continues to debate its exact origin, particularly in the locations where the manoeuvre was allegedly created (e.g., Brazil, Chile, and Peru). Nevertheless, the available facts and dates tell a straightforward narrative, indicating that the bicycle kick's invention occurred in South America, during an era of innovation in association football tactics and skills.

British immigrants, attracted by South America's economic prospects, including the export of coffee from Brazil, hide and meat from Argentina, and guano from Peru, introduced football to the region during the 1800s. These immigrant communities founded institutions, such as schools and sporting clubs, where activities mirrored those done in Britain—including the practice of football. Football's practice had previously spread from Britain to continental Europe, principally Belgium, the Netherlands and Scandinavia, but the game had no innovations in these locations. Matters developed differently in South America because, rather than simply imitate the immigrants' style of play—based more on the slower "Scottish passing game" than on the faster and rougher English football style—the South Americans contributed to the sport's growth by emphasizing the players' technical qualities. By adapting the sport to their preferences, South American footballers mastered individual skills like the dribble, bending free kicks, and the bicycle kick.

Bicycle kicks first occurred in the Pacific ports of Chile and Peru, possibly as early as in the late 1800s. While their ships were docked, British mariners played football among themselves and with locals as a form of leisure; the sport's practice was embraced at the ports because its simple rules and equipment made it accessible to the general public. Afro-Peruvian seaport workers may have first performed the bicycle kick during late 19th century matches with British sailors and railroad employees in Peru's chief seaport, where it received the name tiro de chalaca ('Callao strike'). The bicycle kick could also have been first performed in the 1910s by Ramón Unzaga, a Spanish-born Basque athlete who naturalized Chilean, at Chile's seaport of Talcahuano, there receiving the name chorera (alluding the local demonym).

Chilean footballers spread the skill beyond west South America in the 1910s and 1920s. In the South American Championship's first editions, Unzaga and fellow Chile defender Francisco Gatica amazed spectators with their bicycle kicks. Chilean forward David Arellano also memorably performed the move and other risky manoeuvres during Colo-Colo's 1927 tour of Spain—his untimely death in that tour from an injury caused by one of his acrobatics is, according to Simpson and Hesse, "a grim warning about the perils of showboating". Impressed by these bicycle kicks, aficionados from Spain and Argentina named it chilena, a reference to the players' nationality. During the 1940s, Carlo Parola popularised the use of the bicycle kick in Italian football, earning the nickname Signor Rovesciata ("Mr. Overhead Kick").

Brazilian forward Pelé rekindled the bicycle kick's international acclaim during the second half of the 20th century. His capability to perform bicycle kicks with ease was one of the traits that made him stand out from other players early in his sports career, and it also boosted his self-confidence as a footballer. After Pelé, Argentine midfielder Diego Maradona and Mexican forward Hugo Sánchez became notable performers of the bicycle kick during the last decades of the 20th century. Other notable players to have performed the move during this period include Peruvian winger Juan Carlos Oblitas, who scored a bicycle kick goal in a 1975 Copa América match between Peru and Chile, and Welsh forward Mark Hughes, who scored from a bicycle kick in a World Cup qualification match played between Wales and Spain in 1985.

Since the beginning of the twenty-first century, the bicycle kick continues to be a skill that is rarely executed successfully in football matches. In 2016, the International Federation of Association Football (FIFA) named the bicycle kick as "football's most spectacular sight" and concluded that, despite its debatable origins and technical explanations, bicycle kicks "have punctuated the history of the game".

Iconic status

The bicycle kick retains much appeal among fans and footballers; Hesse and Simpson highlight the positive impact a successful bicycle kick has on player notability, and the United States Soccer Federation describes it as an iconic embellishment of the sport. According to former Manchester City defender Paul Lake, a notable bicycle kick performed by English left winger Dennis Tueart caused injuries to hundreds of fans who tried to emulate it. In 2012, a fan poll from The Guardian awarded English forward Wayne Rooney's 2011 Manchester derby bicycle kick the title of best goal in the Premier League's history. When Italian striker Mario Balotelli, during his youth development years, patterned his skills on those of Brazilian midfielder Ronaldinho and French midfielder Zinedine Zidane, he fixated on the bicycle kick. In 2015 against Liverpool, Juan Mata scored an iconic bicycle kick that secured the win for his team. Portuguese forward Cristiano Ronaldo's Champions League bicycle kick goal, in 2018, received widespread praise from fellow footballers, including English forward Peter Crouch, who tweeted "there is only a few of us who can do that", and Swedish forward Zlatan Ibrahimović, who challenged Ronaldo to "try it from 40 meters"—a reference to his FIFA Puskás Award-winning 2012 bicycle kick goal during an international friendly match between Sweden and England. Gareth Bale's bicycle kick in the 2018 UEFA Champions League final against Liverpool is considered one of the best ever goals.

Some of the most memorable bicycle kicks have been notably performed in the FIFA World Cup finals. German striker Klaus Fischer scored from a bicycle kick in the Spain 1982 World Cup semi-finals match between West Germany and France, tying the score in overtime—the game then went into a penalty shootout, which the German team won. Hesse and Simpson consider Fischer's action the World Cup's most outstanding bicycle kick. In the Mexico 1986 World Cup, Mexican midfielder Manuel Negrete scored from a bicycle kick during the round of 16 match between Mexico and Bulgaria—although overshadowed by "The Goal of the Century" scored by Maradona in the quarter-finals match between Argentina and England, Negrete's goal earned the "World Cup's greatest goal" title by a FIFA fan poll conducted in 2018. Defender Marcelo Balboa's bicycle kick, in the 1994 FIFA World Cup match between Colombia and the United States, received much praise and is even credited with helping launch Major League Soccer in the United States. In the Korea-Japan 2002 World Cup, Belgian attacking midfielder Marc Wilmots scored what English football writer Brian Glanville describes as a "spectacular bicycle kick" against Japan. In the 2022 FIFA World Cup, Brazilian player Richarlison's bicycle kick goal against Serbia was considered one of the best goals of that tournament.

Bicycle kicks are also an important part of football culture. According to the United States Soccer Federation, Pelé's bicycle kick in the 1981 film Escape to Victory is a textbook execution of the skill, and Pelé expressed satisfaction with his attempt to "show off" for the film in his autobiography. A Google Doodle in September 2013, celebrating Leônidas da Silva's 100th birthday, prominently featured a bicycle kick performed by a stick figure representing the popular Brazilian forward. Bicycle kicks have also been featured in advertisements such as a 2014 television commercial where Argentine forward Lionel Messi executes the manoeuvre to promote that year's FIFA football simulation video game. In 2022, FIFA, through its official Twitter account in Spanish, rekindled the controversial origin of the bicycle kick asking users if the maneuver was a "chalaca" or a "chilena" (alluding to the dispute between Peruvians and Chileans).

A monument to the bicycle kick executed by Ramón Unzaga was erected in Talcahuano, Chile, in 2014; created by sculptor María Angélica Echavarri, the statue is composed of copper and bronze and measures three meters in diameter. A statue in honor of Manuel Negrete's bicycle kick is planned for the Coyoacán district of Mexico City. The Uruguayan novelist Eduardo Galeano wrote about the bicycle kick in his book Soccer in Sun and Shadow, praising Unzaga as the inventor. The Peruvian Nobel laureate writer Mario Vargas Llosa has the protagonist in The Time of the Hero's Spanish edition declare that the bicycle kick must have been invented in Callao, Peru.

The manoeuvre is also admired in variants of association football, such as beach soccer and futsal. In 2015, Italian beach soccer forward Gabriele Gori reportedly stated about the bicycle kick that "[i]t comes down to an awful lot of training". An action like the bicycle kick is also used in sepak takraw, a sport whose objective is to kick a ball over a net and into the opposing team's side.

♣ Curl (association football)

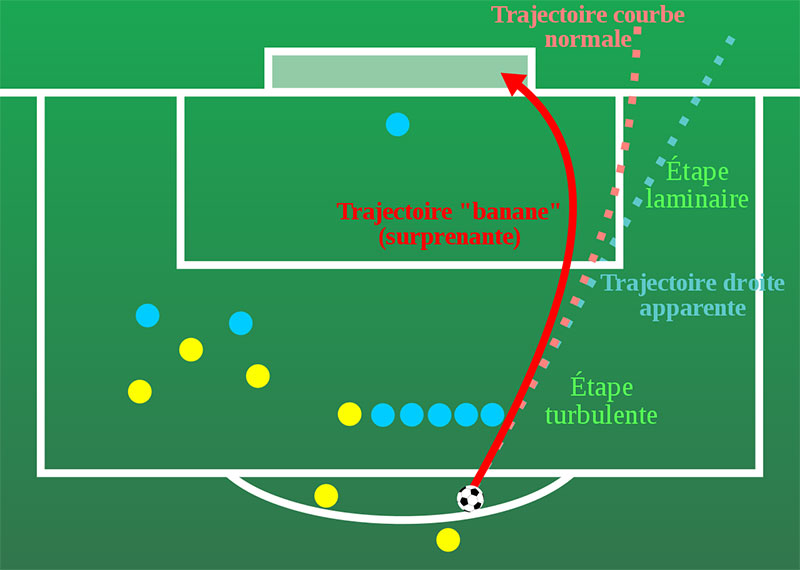

Curl or bend in association football is a definition for a spin on the ball which makes the ball move in a curved direction. When kicking the ball, the inside of the foot is often used to curl the ball, but this can also be done by using the outside of the foot. Similar to curl, the ball can also swerve in the air, without the spin on the ball which makes the ball curl.

Curling or bending the ball is especially used in free kicks, shots from outside the penalty area and crosses. Differences between balls can affect the amount of swerve and curl: traditional leather footballs were too heavy to curl without great effort, whereas lighter modern footballs curl more easily.

Nomenclature

The deviation of a ball from the straight path in the air is known as the curl, or swerve; however, the spin on the ball that causes this is also known as the curl. Shots that curl, bend, or swerve are known as curlers, or in extreme cases, banana shots. The technique of putting curl on a ball with the outside of the foot is sometimes known as a trivela, a Portuguese term, with Ricardo Quaresma a notable user of this skill. The topspin technique of putting straight curl (instead of side curl) on a ball is known as a dip or dipping shot. Putting no spin on the ball is often used for longer distance kicks, and can cause the ball to dip, or wobble in the air unpredictably. The 1950s Brazilian star Didi is thought to have invented this technique, and used it frequently when taking free kicks, which were known as folha seca ("dry" or "dead leaf," in Portuguese) free kicks. Today it is commonly known as the knuckleball technique; this technique has also been described in the media as the "tomahawk", or even the "maledetta" ("accursed," in Italian).

Usage

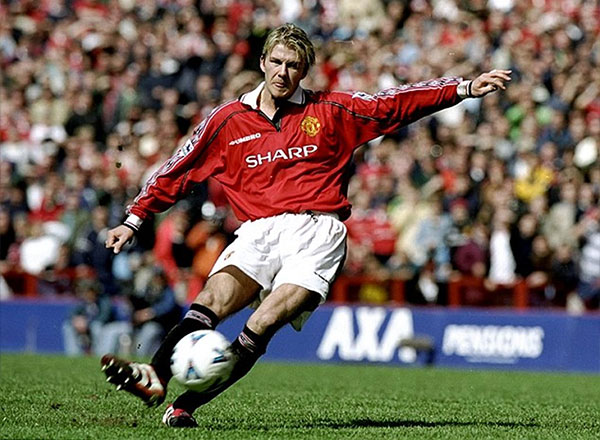

Free kicks

Free kick takers often curl and put spin on the ball, to curl it over or around the wall of defending players, out of the reach of the goalkeeper. Goalkeepers usually organize walls to cover one side of the goal, and then stand themselves on the other side. Thus, the free kick taker has several choices, from curling the ball around the wall with finesse, to bending the ball around the wall using power, or even going over the wall—although this last lessens the likelihood of scoring from close range.

The 1950s Brazilian star Didi is widely believed to have invented the folha seca technique; however, Italian forward Giuseppe Meazza before him is also credited with using the technique. Today, the knuckleball technique is notably used by modern-day players such as Juninho (whose technique has often been emulated), and Cristiano Ronaldo, who would strike the ball with either no or a low amount of spin, causing it to swerve unexpectedly at a point near the goal. Gareth Bale and Andrea Pirlo are also notable proponents of this technique when taking free-kicks.

Corners

Curling can be an effective technique when taking corners. The ball gradually moves in the air towards the goal. This is referred to as an in-swinging corner. Occasionally, a corner-taker will bend the ball towards the edge of the penalty area, for an attacker to volley, or take a touch and then shoot. Rarely, a goal can be scored directly, this is called an "Olympic goal" and it requires amazing technique and a distraction of the opposing goalkeeper.

Passing

Curling can be used in passing. Effective passes from midfield to an attacking player are often the result of a curled pass around the defender, or long cross-field passes are sometimes aided by the addition of curl or backspin. This can be done with either the inside of the foot or outside of the foot. The outside of the foot may be used when a player is facing sideways and wants to use the dominant foot to make a pass; this technique is known as the trivela.

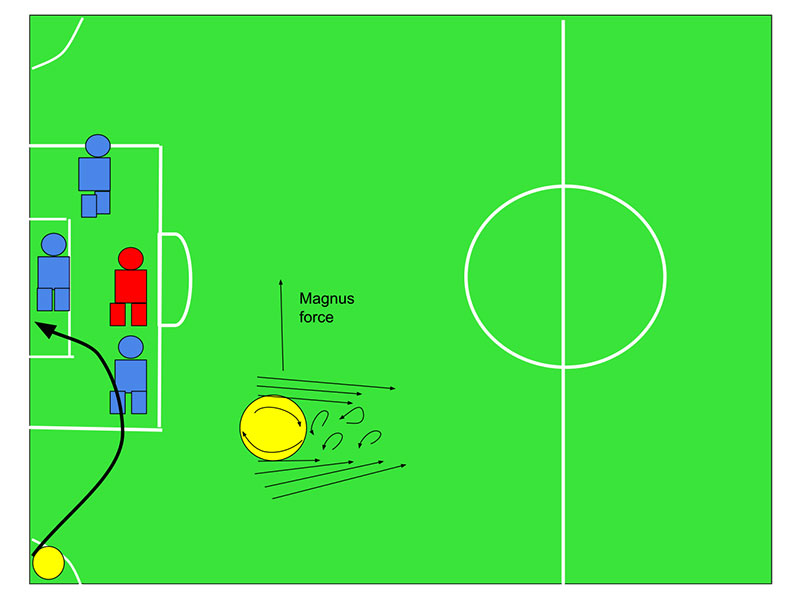

Causes

The fact that spin on a football makes it curl is explained by the Magnus effect. In brief, a rotating ball creates a whirlpool of air with itself at its center. Thus, the air on one side of the ball moves in the same direction the ball is traveling in, and the air on the other side moves in the opposite direction. This creates a difference in air pressure around the ball, and it is this sustained difference in pressure which causes the course of the ball to deviate.

The Magnus effect is named after German physicist Heinrich Gustav Magnus, who described the effect in 1852. In 1672, Isaac Newton had described it and correctly inferred the cause after observing tennis players in his Cambridge college.

Notable players

Many football players are renowned for their ability to curl or bend the ball when passing or shooting at goal, either from open play or a free kick. These include: Pelé, Didi, Rivellino, Zico, Diego Maradona, Michel Platini, Roberto Baggio, Alessandro Del Piero, Gianfranco Zola, Michael Gregoritsch, Siniša Mihajlović, Zinedine Zidane, Rivaldo, David Beckham, Roberto Carlos, Juninho, Ronald Koeman, Andrea Pirlo, Ricardo Quaresma, Gareth Bale, Philippe Coutinho, Ronaldinho, Thierry Henry, Neymar, Kaká, Miralem Pjanić, Rogério Ceni, Shunsuke Nakamura, Pierre van Hooijdonk, Hristo Stoichkov, Thomas Murg, Luis Chávez, Carlos Vela , Cristiano Ronaldo, Luka Modrić, Giuseppe Meazza, Ángel Di María, Kevin De Bruyne and Lionel Messi, among others.

♣ Rabona (association football)

In association football, the rabona is the technique of kicking the football where the kicking leg is crossed behind the back of the standing leg.

There are several reasons why a player might opt to strike the ball this way: for example, a right-footed striker advancing towards the goal slightly on the left side rather than having the goal straight in front may feel that his shot power or accuracy with his left foot is inadequate (more colloquially, the player has "no left"), so will perform a rabona in order to take a better shot. Another scenario could be a right-footed winger sending a cross while playing on the left side of the pitch without having to turn first. Another reason why a player could perform a rabona might be to confuse a defending player, or simply to show off their own ability, as it is considered a skillful trick at any level.

History

Rabona in Spanish means to play hooky, to skip school. The name derives from its first documented performance by Ricardo Infante in a game between Estudiantes de la Plata and Rosario Central in 1948. The football magazine El Gráfico published a front cover showing Infante dressed as a schoolboy with the caption "El infante que se hizo la rabona" (In English: "The kid who plays hooky"). Another supposed origin for the name is that Rabona is derived from the Spanish word rabo for tail, and that the move resembled the swishing of a cow's tail between or around its legs. In Brazil, the move is also known as the chaleira (kettle) or letra (letter).

The first filmed rabona was performed by Brazilian footballer Pelé in the São Paulo state championship in 1957. Giovanni "Cocò" Roccotelli is credited with popularising the rabona in Italy during the 1970s; at the time, this move was simply called a "crossed-kick" (incrociata, in Italian).

In addition to the aforementioned players, some examples of various well known exponents of the rabona, who have successfully performed the skill in competitions and are also known to employ it frequently during matches, are: Fernando Redondo, Alan Ball, Diego Maradona, Romário, Roberto Baggio, Cristiano Ronaldo, Pablo Aimar, Raúl Jiménez, Claudio Borghi, Matías Fernández, Matías Urbano, Mário Jardel, David Villa, Ariel Ortega, Robinho, Alberto Aquilani, Pablo Aimar Eden Hazard, Joe Cole, Ronaldinho, Ángel Di María, Rivaldo, Ricardo Quaresma, Erik Lamela, Pablo Aimar, Gianfranco Zola, Roberto Carlos, Matthew Kowalczyk, Neymar, Luis Suárez, Jay-Jay Okocha.

Other players who have also used this skill successfully during a competitive match are: Amr Elsolia, Andrés Vasquez, Djalminha, Fahad Al Enezi, Thomas Müller, Manolis Skoufalis, Léo Lima, Marcos Rojo, Érik Lamela (once in the River Plate youth sides, once in 2014, and once in 2021), Marcelo Carrusca, Jordan Henderson, Dimitri Payet, Carlos Bacca, Fabrizio Miccoli, Mario Balotelli, Jonathan Calleri, Diego Perotti, Mikael Lustig, Eran Zahavi, Robert Lewandowski, and Jaden Philogene, among many others; Johnny Giles of Leeds United also performed one in the famous sequence of possession against Southampton in 1972 during a 7–0 win.

♣ Scorpion kick (association football)

The scorpion kick, also known as a reverse bicycle kick or back hammer kick, is a physical move in association football that is achieved by diving or throwing the body forwards and then placing the hands on the ground to lunge the back heels forward to kick an incoming ball. Sports historian Andreas Campomar praises the maneuver as remarkable, noting that it "demonstrated that the spectacle had not died: that the game, in spite of its many flaws, could provide moments of glory that had little to do with just victory or defeat."

The move gets its name from the player's resemblance to a scorpion's tail while performing the kick.

Colombian goalkeeper René Higuita is attributed with the invention of this skill. One of his best known performances of the maneuver occurred at Wembley Stadium during a 1995 international friendly match between Colombia and England.

On top of the regular diving scorpion kick, there are also other variations such as standing scorpion kick and spinning scorpion kick, neither of which necessarily result in the hands being placed on the ground. Swedish forward Zlatan Ibrahimović is a notable exponent for the standing scorpion kick, while the Italian defender Giuseppe Biava is a notable exponent for the spinning scorpion kick.

Recommend Channel

World National football team squads

Football Instagram Photo Gallery

© SportsLib. All rights reserved